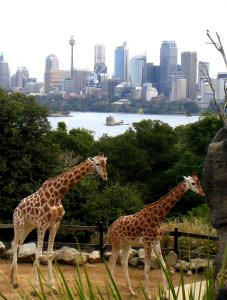

The only creatures [Irwin] couldn't dominate were parrots. A parrot once did its best to rip his nose of his face. Parrots are a lot smarter than crocodiles. The Australian public is eagerly waiting. Thousands have camped out for a few days for an allotment of 3000 free tickets. The occasion is Steve Irwin's memorial service to be held on Wednesday, 20 September at his Australia Zoo. John Williamson is scheduled to play. The service will be screened before a worldwide TV audience. The "crocodile hunter" (a title used by his fans without self-irony) was dead, killed by the jab of a docile stingray off Port Gladstone on 4 September while filming a documentary. The story of his life, already being written, will conclude that he was a good conservationist, a global ambassador for protecting "dangerous" animals. But can the owner or manager of a zoo ever claim such a title? Zoos: cordoned off spaces, celebrating the subjugation of nature. They demonstrate a cruel pecking order: you are on show, it tells animals, because you are in captivity, because you are not free, and your ancestors were exterminated. You must sing for your supper; you must perform for the public. If natural conservation is dependent on the televisual orgy, the gladiatorial contest (Will Steve be eaten? Will the reptile eat Steve's child?), we must be desperate indeed. The images he produced are akin to those that shaped the West's consciousness of the developing world: the dying child, the famine-stricken family. In many ways, both sequences are tasteless: they denigrate their subject in the name of publicity. Mark Townsend of the Queensland branch for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals must be mistaken to assume that Steve was "a modern-day Noah" (6 September). Perhaps the lesson is this: the animal world is there for the picking, an entertainment bonanza. Preserve it, yes, but only do so at the cost of its solitude and tranquillity. Those in favour of Irwin's environmentalism cite his purchasing ventures: he bought tracts of land for "conservation". Perhaps he was more complicated than his fans realise. Irwin, who always realised environmental projects as business ventures, never wavered in his central philosophy: reduce the beings of the animal kingdom to anthropomorphic caricatures: crocodiles and snakes can be handled, cuddled, kissed. Their existence in enclosures implies a loss of sanctuary, not an affirmation of conservation. Reactions like those of the American organisation, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals are dismissed with the headlines: "US Activists dancing on Star's Grave" (14 September). The melody they dance to is ignored as macabre and insincere. "He made a career out of antagonising frightened wild animals, which is a very dangerous message to kids," warned PETA activist Dan Matthews. Its spokeswoman Lisa Wothne added her support in an interview with News Limited, encouraging a boycott of Australia Zoo whilst discouraging Irwin's children from imitating their late father. A large swathe of international scientific and environmental opinion has also been ignored—what would they know? Even if Irwin's treatment of animals was of no consequence to his legions of fans, his treatment of the ray in his last moments could have shed some light. A debate grew up on whether a video filming his last moments would be released. But his management preferred to nourish the legend of the environmentalist rather than the one he was most known for: the "croc" hunter who may have died aggravating an otherwise placid sea creature.

— Germaine Greer, Guardian, 5 September, 2006 When one sees the praise heaped on this man, it is fitting to bear in mind the historical raison d'etre of zoo keeping: displays of power through entertainment, imparting knowledge on people about their status in society. Whether it was the Chou Dynasty in the 12th century BCE or the biologically-crazed nobles of Europe during the Enlightenment, animals were exotica, symbols of power. The agents of Imperialism, assisted by improved technologies, caged the animals of colonies first in private menageries, then public exhibition spaces called zoos. By the late 19th century zoos were no longer elitist. Democratised (Irwin was "egalitarian", one of "us" and the great leveller), the zoo became a space of civic virtue. The public could see the wonders of the "wild".

When one sees the praise heaped on this man, it is fitting to bear in mind the historical raison d'etre of zoo keeping: displays of power through entertainment, imparting knowledge on people about their status in society. Whether it was the Chou Dynasty in the 12th century BCE or the biologically-crazed nobles of Europe during the Enlightenment, animals were exotica, symbols of power. The agents of Imperialism, assisted by improved technologies, caged the animals of colonies first in private menageries, then public exhibition spaces called zoos. By the late 19th century zoos were no longer elitist. Democratised (Irwin was "egalitarian", one of "us" and the great leveller), the zoo became a space of civic virtue. The public could see the wonders of the "wild". It has been just two weeks since his death, and already the hagiographic glow that emanates from the sepulchre of Australia Zoo is overwhelming. Australians like Irwin in spite of themselves, lamenting his fall the way the ill-planned expedition of Burke and Wills is lamented. Nature, we assume, is there to be conquered. Sometimes it proves cruel, but the pound of flesh it extracts from humankind is repaid ten-fold. A week after his death, Wayne Sumpton of the state fisheries department announced that ten stingrays had been found, their bodies mutilated.

It has been just two weeks since his death, and already the hagiographic glow that emanates from the sepulchre of Australia Zoo is overwhelming. Australians like Irwin in spite of themselves, lamenting his fall the way the ill-planned expedition of Burke and Wills is lamented. Nature, we assume, is there to be conquered. Sometimes it proves cruel, but the pound of flesh it extracts from humankind is repaid ten-fold. A week after his death, Wayne Sumpton of the state fisheries department announced that ten stingrays had been found, their bodies mutilated.

Zookeeper Irwin preached the wrong message

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment